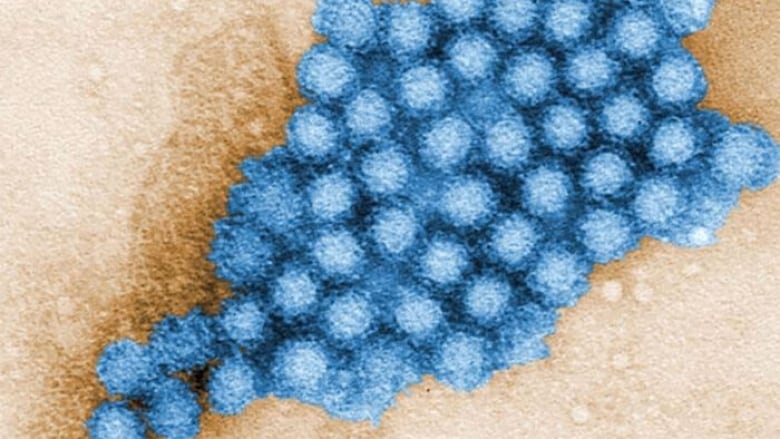

Highly contagious norovirus, known for causing a nasty, days-long stomach illness, is on the rise in Canada after a pandemic lull, federal health officials confirmed.

Since early January, reported cases of norovirus have been “increasing both at the national level and within several provinces,” including British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) said.

Infections identified through PHAC’s surveillance program since the start of 2023 are “generally comparable” with those reported during the same time period in the last few seasons prior to the pandemic, said spokesperson Anna Maddison. PHAC did not provide hard data, due to the “preliminary nature” of the figures being reported by the provinces.

Given the unpleasant, and in some cases deadly, symptoms — including stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, and dehydration — the virus’s rise in Canada offers another rude reminder of how many pathogens are circulating again this winter.

“What we’re seeing are the numbers of infections returning to what was the normal baseline before the pandemic,” said Lawrence Goodridge, a professor of microbiology at the University of Guelph and an expert in food safety and norovirus surveillance.

For much of the last few years, COVID-19 restrictions and infection prevention measures like handwashing and mask-wearing likely helped keep norovirus at bay, all while people were circulating less than usual, he said.

“But as things have been relaxed, and things have opened up, and things are getting back to normal, we’re beginning to see [more cases].”

Cases up in U.S., U.K.

South of the border, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recently reported a rise in cases nearly reaching pre-pandemic levels.

From August to early January, 225 norovirus outbreaks were reported by states participating in a federal surveillance program, CDC data shows. That’s compared to 172 norovirus outbreaks reported by the same states during the same period last season.

And in the U.K., norovirus is also back with a vengeance, with national surveillance data showing lab reports of the virus are 66 per cent higher than the average for this time of year.

Care homes are experiencing a rise in outbreaks, and the biggest increase in cases is among people aged 65 and up, the UK Health Security Agency said in a release.

“While high numbers of cases in this age group is expected at this time of year,” the agency continued, “these levels haven’t been seen in over a decade.”

Norovirus typically spreads through contaminated foods, such as raw shellfish or imported fruit, and is also highly transmissible in closed settings, including households, care homes, cruise ships and daycare facilities.

In 2022, B.C. oysters were linked to hundreds of cases in several provinces and in parts of the U.S., largely among people who’d eaten contaminated raw oysters between January and March that year.

“It can really spread like wildfire, just because it is a very, very infectious virus — you don’t have to be exposed to very much of it at all to get an infection,” said virologist Angela Rasmussen from the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization.

“And unfortunately, when you’re infected with norovirus, you have pretty severe gastroenteritis most of the time, and that leads to shedding [the virus] … hopefully into the bathroom around you. But when people don’t wash their hands, you can contaminate other surfaces.”

The onset of the illness is typically quite sudden, said Christiane Wobus, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at University of Michigan.

“If you had contact with someone who was sick,” she said, “within 12 hours you can show symptoms.”

Handwashing, cleaning surfaces can curb transmission

Long known as the “winter vomiting disease,” norovirus spreads in the Northern Hemisphere largely between November and April, when people are spending more time indoors.

Unlike some other viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind COVID-19, norovirus is particularly hardy on surfaces, Goodridge said.

Key ways to curb transmission include handwashing, cleaning shared surfaces, isolating as much as possible from others at home, and keeping family members out of school and work if they’re experiencing symptoms.

Family physician Dr. Allan Grill, the chief of family medicine at Markham Stouffville Hospital in Markham, Ont., said it’s also important to keep an eye on vulnerable loved ones, including frail seniors and — in particular — children, who may be at a higher risk of getting dehydrated.

“Are they not feeding as well? Do they have [fewer] wet diapers over 24 hours?” he said.

In those cases, it’s important to keep kids hydrated by giving them lots of fluids, and taking them to primary care or an emergency department if their symptoms don’t improve within a few days.

Since many people with stomach bugs don’t ever set foot in a doctor’s office — and those who do might not necessarily be tested — Grill said the number of cases in any given year are likely an undercount. (Federal figures suggest norovirus sickens more than a million Canadians each year.)

To spot norovirus outbreaks more quickly, Goodridge and other researchers are trying to use wastewater surveillance to improve monitoring efforts — work that he said was “derailed” in the pandemic as all eyes turned to COVID-19, but is now back on track.

“We are increasingly looking for other foodborne pathogens now as the pandemic ends,” he said.

Redes Sociais - Comentários