Canada’s nursing homes have worst record for COVID-19 deaths among wealthy nations: report

Canada has the worst record for COVID-19 deaths in long-term care homes compared with other wealthy countries, according to a new report released on Tuesday by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Head of private long-term care company resigns after hundreds of deaths in Ontario homes

The study found that the proportion of deaths in nursing homes represented 69 per cent of Canada’s overall COVID-19 deaths, which is significantly higher than the international average of 41 per cent.

In Canada, between March 2020 and February 2021, more than 80,000 residents and staff members of long-term care homes were infected with the coronavirus. Outbreaks occurred in 2,500 care homes, resulting in the deaths of 14,000 residents, according to the report.

“COVID-19 has exacted a heavy price on Canada’s long-term care and retirement homes, resulting in a disproportionate number of outbreaks and deaths,” the report’s introduction says.

The study, which primarily focused on the first six months of the pandemic, found that across the country, nursing home residents received less medical care. They had fewer visits from doctors, and there were also fewer hospital transfers when compared with other years.

Researchers also looked beyond the coronavirus to all deaths in care homes.

“Resident deaths — for all causes, not just from COVID-19 infection — increased by 19 per cent in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador,” the report said. “There were 2,273 more deaths than the average in the five years prior to COVID-19, with the largest increase occurring in April 2020.”

Last spring, Ontario experienced the largest increase in “excess deaths” at 28 per cent, while B.C. had the smallest at just four per cent, the study found.

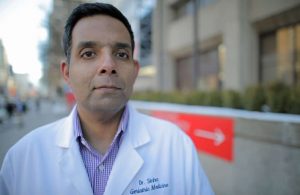

“It really tells us that there were things that we could have done to avoid a lot of the deaths that we saw in Canada and that countries, frankly, that were better prepared prior to the pandemic, that had better funded systems, they performed far better than Canada has,” said Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research and co-chair at the National Institute on Ageing, a partner in the study with CIHI.

“Relative to other nations in the world, Canada has actually the worst record overall.”

Family among those locked out of care facilities

With lockdowns and forced isolation, those living in care homes also had less contact with friends and family.

Mae Wilson is among the statistics.

The 93-year-old was one of the thousands of long-term care residents who died in 2020 after her Eastern Ontario nursing home, Almonte Country Haven, was overcome by a COVID-19 outbreak — with 72 of 82 residents contracting the disease.

Wilson, a former nurse, was one of 29 residents to die last spring from COVID-19.

“I really want people to feel uncomfortable about the way they’ve treated our seniors. Not just my mom, all of them,” said her son, Grant Wilson. “I’m still angry about it.”

The study’s authors found that during the first wave last spring, the total number of resident deaths was higher than in the years prior to the pandemic, even in places with fewer COVID-19 deaths.

“The proportion of residents who had no contact with a loved one tripled in the first wave, compared with previous years. Residents who had no contact with family and friends were more likely to be assessed with depression,” the report said.

But it appears that lessons learned in the first wave didn’t lead to changes in outcomes during the second wave last fall, which was “bigger and broader” in Canada, resulting in “a larger number of outbreaks, infections and deaths.”

The study found that the number of COVID-19 infections among nursing home residents increased by 62 per cent in the second wave compared with the first.

The report singled out Ontario and Quebec, noting that they “had the largest proportion of homes with outbreaks involving resident cases.” It also said that during the pandemic’s first wave, “more than one-third (34 per cent) of all Ontario LTC homes and 44 per cent of all Quebec LTC homes experienced an outbreak with at least one resident case.” Those numbers compare with just eight per cent of long-term care homes in B.C. and 17 per cent in Alberta.

“Did we have a number of avoidable deaths? Absolutely. Could they have been prevented? Absolutely,” said Sinha, who is also director of geriatrics at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

National standards urged for homes

Several provincial inquiries are now underway in an attempt to figure out what happened in long-term care homes during the pandemic and to recommend changes.

Staffing continues to be an issue.

“All of the inquiries have said staff are important, having a medical director on the floor is important, having everybody understand what infection prevention and control precautions are and to use them uniformly, all those things are considered really important,” said Tracy Johnson, director of health system analysis at CIHI.

The report said that during the first wave, staffing shortages at long-term care homes “were exacerbated in parts of Canada as a result of staff illness due to COVID-19 and higher absenteeism rates.

In response, the report said, more than 1,500 members of the Canadian Armed Forces were deployed to 32 of the “most severely impacted homes” in Ontario and Quebec last spring and reported “poor infection prevention and control practices (e.g., insufficient medical supplies and training, personal protective equipment not available), residents being ‘denied food or not fed properly’ and extensive staffing problems.”

During last year’s throne speech, the federal government promised to set new national standards for long-term care, but new rules have yet to materialize.

“We do like national standards, but that will be up to the federal government and the provinces to decide,” Johnson said. “That’s the discussion I think all of them are in right now, and the provinces very much feel that that’s their territory.”

Redes Sociais - Comentários