Downplaying dangers of COVID-19, taking research out of context are common strategies, experts say.

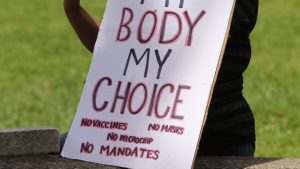

As more regions across the country adopt mandatory masking policies in an effort to minimize the spread of COVID-19, some anti-masking groups are joining forces with anti-vaccination proponents and adopting their techniques to spread misinformation and amplify their message.

The similarities between organized anti-masking and anti-vaccine movements are striking, said Maya Goldenberg, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Guelph specializing in vaccine hesitancy.

At least one anti-masking group, Hugs Over Masks, actively partners with Vaccine Choice Canada, one of the country’s most prominent anti-vaccination organizations.

Vladislav Sobolev, the anti-masking group’s founder, has repeatedly praised the anti-vaccination group on social media and during protests.

Sobolev also told CBC News that high-profile U.S. anti-vaccination advocate Sherri Tenpenny, an osteopath who wrote Saying No To Vaccines, is providing online leadership training to his group.

Tenpenny, along with other anti-vaccination advocates in the U.S. and Canada, have embraced the anti-masking cause and opposed COVID-19 lockdown measures.

Although many Canadians who don’t want to wear masks aren’t opposed to vaccines, the fact that anti-vaccination groups are involved in the relatively new anti-masking movement is concerning to many health experts.

Despite well-established evidence that vaccines are safe and effective, anti-vaccination groups have become savvy at spreading misinformation that leads people to distrust medical guidance — something that can have dire consequences during a pandemic.

‘Harmful outcomes’

“It disturbs me when I see people acting on information that I’m quite sure is not only incorrect, but potentially misleading and potentially leading to harmful outcomes,” said Dr. Matthew Oughton, an infectious disease specialist at McGill University.

As a practising physician at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, Oughton has seen first-hand the toll COVID-19 takes. Close to 9,000 people — largely seniors and people with underlying medical conditions — have died in Canada from the virus.

Although scientists are continuing to learn about the novel coronavirus, it appears that people with COVID-19 can be most infectious before they show any symptoms, Oughton said.

That’s different from many other viruses — including the first version of SARS. It’s a key reason why it’s important for people to wear masks — even if they feel perfectly healthy — when physical distancing isn’t possible to prevent transmission, medical experts say.

Mistrust of health authorities fuels misinformation

Mistrust of government and scientific authorities are key characteristics among both anti-vaccination and anti-masking advocates, Goldenberg said.

“When you don’t trust the sort of basic infrastructure that’s supposed to support public well being, you’re going to come up with all kinds of tactics to try to resist it,” she told CBC News. Those tactics include the “downplaying of how bad the infectious disease is,” Goldenberg said.

Before COVID-19, anti-vaccination groups were making false claims that measles — a serious, vaccine-preventable disease — wasn’t a major threat. A consequence of that misinformation was an increase in vaccine hesitancy, leading to a resurgence of measles cases in Canada, where it had been declared eliminated in the late 1990s.

Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-vaccination and anti-masking groups have claimed that coronavirus isn’t any more dangerous than other diseases, such as the flu. This is part of an effort to falsely convince people that public health measures to stop the spread of infection — from the development of a vaccine to physical distancing and wearing a mask — are unnecessary.

Many social media posts from both anti-masking and anti-vaccination groups call the pandemic a conspiracy, citing beliefs that it’s been manufactured to give governments the ability to monitor people through contact tracing and to promote a vaccine agenda. Both groups often target Bill Gates, whose foundation has donated hundreds of millions of dollars to support immunizations globally. When asked if Hugs Over Masks opposes vaccination, Sobolev did not answer directly.

“The right for an individual to have the choice on any medical intervention set forth by the public health departments is especially important when there are undeniable and inherent risks associated with the intervention in question,” he said in an emailed response. “Health Freedom is not something that should be even in question.”

The group actively defies public health guidance during rallies, where people are encouraged to bring their children, reject physical distancing and not wear masks, saying that they refuse to adopt the “new normal” of life during the pandemic. Anti-masking rallies in Toronto appear to attract anywhere from a couple of dozen to around 150 people.

Sobolev said his group consider COVID-19 a “scamdemic,” arguing Canada’s hospitals would have been filled to capacity with COVID-19 patients if it were real.

When CBC News suggested that the success of the public health measures his group was protesting were a reason more people didn’t become critically ill, Sobolev said he didn’t trust the numbers. He said people should look at South Dakota, which didn’t have a state-imposed lockdown.

Lawsuit alleges vaccine conspiracy

Vaccine Choice Canada, along with several individual plaintiffs, filed a statement of claim at the Ontario Superior Court of Justice this month against public health and political leaders in several municipalities, as well the province of Ontario and the federal government, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Theresa Tam and the Queen.

The lawsuit claims COVID-19 public health measures, including lockdowns, physical distancing and mandatory masking are violations of constitutional rights. It also claims that the pandemic was unnecessarily declared to further “non-medical agendas,” including to establish a “New (Economic) World Order” and a “massive and concentrated push for mandatory vaccines of every human on the planet earth with concurrent electronic surveillance.”

Canadian public health officials have never suggested that a coronavirus vaccine, when developed, would be mandatory. The lawsuit also names the CBC, accusing it of “Stalinist censorship” by “knowingly refusing to cover/or publish the valid and sound criticism of the COVID measures.” It’s not clear when — or whether — the lawsuit will proceed through the courts.

‘Cherry-picking’ data

Another commonly used tactic by both anti-masking and anti-vaccination organizations is “cherry-picking” research studies that appear to support their viewpoint, but are often outdated or taken out of context, said McGill University’s Dr. Oughton.

For example, anti-masking groups often incorrectly claim that wearing a mask is harmful because it reduces the supply of oxygen and causes people to breathe toxins back into their own body. That’s misinformation with no basis in fact, Oughton said.

“Surgeons wear these kinds of procedural masks in the operating theatre for, sometimes, hours and hours at a time. The surgeons are not dropping [from lack of oxygen]. They simply aren’t,” he said.

Another piece of false information that anti-maskers have been circulating is the idea that wearing a mask can harm a child’s immune system — a claim Sobolev made to CBC News during a telephone interview.

Those kinds of “alarmist stories” playing into people’s fears about their children’s health are another way anti-vaccine and anti-masking groups try to further their agendas, said Goldenberg, the vaccine hesitancy expert.

Unlike combating vaccine misinformation, where the science has been clear for years, public health experts trying to correct mask misinformation are dealing with some confusion: their recommendations changed over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anti-masking groups have seized upon that inconsistency and frequently cite public health officials from before the mask guidance changed.

Emerging research, changing guidance

Public health experts say they understand the confusion and how it could foster doubt in the current advice. They emphasize that it’s an example of how quickly they’ve been learning about a new virus.

Back in March when the pandemic was first declared, there wasn’t much scientific evidence to demonstrate mask effectiveness in preventing COVID-19, public health experts say.

Physical distancing was also a new concept. Public health officials worried people would think using masks meant they didn’t have to pay as much attention to staying two metres apart from others. Since then, more studies have been done, said Dr. Lawrence Loh, medical officer of health for Peel Region, near Toronto.

“The science in respect to COVID-19 has evolved and so has the recommendation around masks,” Loh said. Once scientists learned the virus could be spread by people with no symptoms through respiratory droplets, they began advising the general public to wear non-medical masks when physical distancing isn’t possible, he added.

There are legitimate medical issues — including some mental health or developmental conditions — that preclude some people from wearing masks, said Dr. Vinita Dubey, Toronto’s associate medical officer of health.

City bylaws do not require people to provide proof of a medical exemption, Dubey said, but she hopes people will only claim an exemption if it’s legitimate. People who simply don’t want to wear masks should pursue alternatives to going into stores, she said, such as curbside pickup.

As an emergency physician who regularly wears a mask at work, Dubey recognizes that masks take some getting used to and can feel uncomfortable at first, but she recommends people try different types if that’s the case.

The data is still not clear on how much masks prevent infection for the wearer, public health experts said.

But that’s why it’s important for as many people as possible who can wear masks to do so when physical distancing isn’t possible, Dubey said. The idea is that people protect others — especially those who are vulnerable to critical illness if they become infected — from their own germs given the possibility of asymptomatic transmission.

“I protect you with my mask; and you protect me with your mask.”

Like with hard-core anti-vaccination groups, people who are adamantly against masking “are a loud but typically smaller proportion of the population,” Dubey said.

The key is to combat the misinformation they spread to members of the public who might be “mask-hesitant” — similar to people who are vaccine-hesitant — by providing clear, honest answers to their questions, experts said. “It’s those who are sitting on the fence who are actually rightly looking for information. We need to reach them and give them the information that they need at the right time,” said Dubey.

“That’s the group that we need to spend most of our energy on,” she said, urging the public to ask health-care providers or public health authorities for information if they have questions.

It’s important for medical professionals to be respectful when people ask those questions — including when they raise concerns based on misinformation, Goldenberg said.

“If there’s one way to get people defensive, it is to disparage them and not to take them seriously,” she said.

CBC/MS

Redes Sociais - Comentários